Building Languages in Games: An Interview with Dr. Jessica Sams

There were several things that annoyed me about Final Fantasy X: Blitzball, Tidus’s whiny voice, the fact that it spawned that awful piece of fan service disguised as a sequel. But there was one thing that both annoyed and puzzled me. The Al Bhed.

This text was written by Megan Condis for Unwinnable in 2016 and reprinted here with permission. Thanks, Megan!

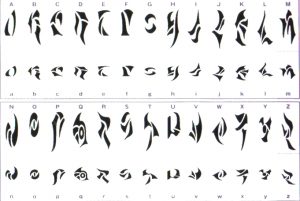

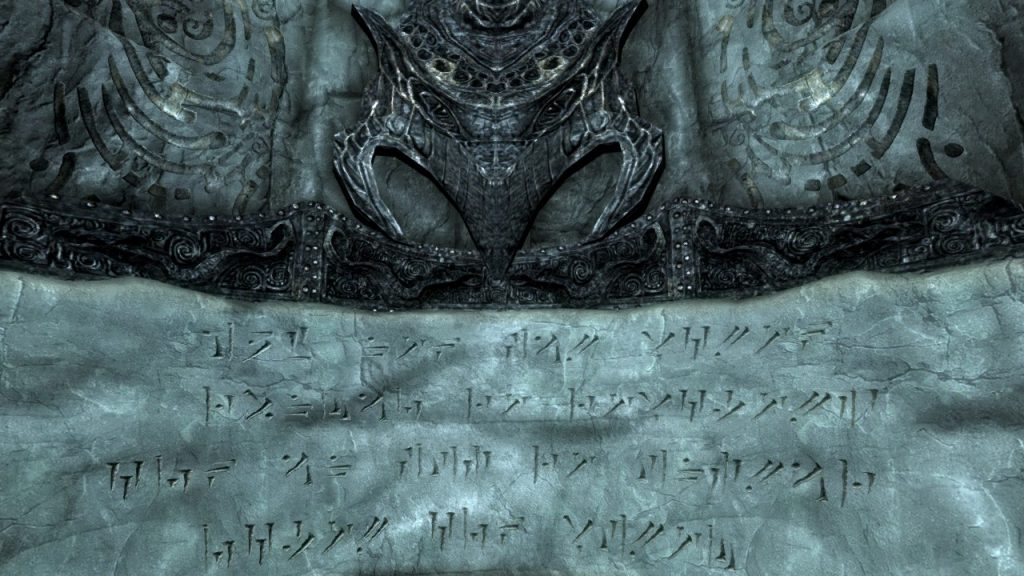

A substitution cipher, just like Al Bhed. Source: thuum.org.

And no, I don’t mean that I was confused by Rikku’s desert machinist culture. Rather, I didn’t get their language. Or I suppose I should say their “language.” Because the Al Bhed don’t actually speak a different tongue from the other cultures on Spira. They employ a simple substitution cipher wherein one letter is consistently swapped with another (think: the daily cryptoquote puzzles in your local newspaper). They weren’t really speaking their own language. They were speaking in code. Didn’t the game designers understand the difference?

Other games approach language creation in different ways. Simlish, the upbeat chattery gibberish in The Sims, is rumored to be “a mixture of Ukranian, Navajo, Romanian, Irish,” and a just dash of nonsense mixed in for good measure.

Still others take a more ambitious route. Blizzard Entertainment maintains a dictionary for the alien language Khalani, spoken by the Protoss in the StarCraft series that fans have attempted to parse, and BioWare’s Dragon Age series features several invented languages such as his own versions of Elvish and Dwarven and the Qunari language, Qunlat, each of which has an extensive vocabulary developed by linguist Wolf Wikeley (who also invented the language Tho Fan for the game Jade Empire).

These invented languages are more than lists of made up words. They require structure and grammar and the development of a new writing system, which in turn are influenced by culture and even morphological features of the creatures who speak them. The art of language construction, in other words, is also a science.

Dr. Jessica Sams, teaches an advanced undergraduate course “Invented Languages” at Stephen F. Austin State University. I was lucky to be able to snag her for an interview so I could ask her about how these monumental linguistic undertakings can help game developers create a more immersive world.

Megan Condis: How did you become interested in the topic of invented languages?

Dr. Jessica Sams: I was in elementary school when one of my teachers had us do an activity where we basically created a code for English. It was by no means an actual invented language (or ‘conlang’, which is short for ‘constructed language,’ the technical term) because it was just another form of English, but it made me fall in love with the process of actually creating words.

I worked on my coded language for about a year, but then it fell by the wayside when I couldn’t get any of my friends interested in learning it. However, my love for creating language-type things was planted then. It grew when that same teacher a few years later introduced me to an Esperanto translation exercise. Doing those types of activities really helped me discover a love for language in general and a love for creating languages.

I didn’t create my first full conlang until 2008 when I had an idea for a novel that needed a language no one else had ever heard. And so I set to work filling out the constructed culture (or conculture) of the speakers before I worked on the language itself. I stopped actively building the language in 2012 (as I had moved on to other languages), but it remains close to my heart because it was my first.

It quite honestly wasn’t until after I had worked on my own conlangs that I became more interested in the conlangs already existing, such as J. R. R. Tolkien’s languages. (While I had exposure to Esperanto, I hadn’t been interested in learning too much more of it/about it—beyond the fun translation exercises—until I worked on my own languages.) Creating a language myself gave me a much deeper appreciation for the art of conlanging.

MC: How does the process of inventing a fictional language contribute to world building?

JS: They feed into each other. You can’t create a language until you understand the world it’s being spoken in and the speakers who are going to use it. I tell my students that a solid language cannot be created in a vacuum. Creating the language, though, also feeds into world building because, as you’re working on aspects of the language, you start realizing that you need to know more or have more context.

For example, I wanted to create a language for garden gnomes (I have several gnomes and wanted them to be able to speak to each other—yes, I’m that person). However, I needed to understand their history, their culture before I could begin to pull together information about the language they

might speak. I started with a general backstory—they were originally humans and part of a warlike Gothic tribe, so their language would be heavily based in the Gothic language.

However, from there, I needed to know where they had been since then and what influences they might have had on their language/culture. Rarely do languages get so isolated that they will have zero outside influence on their development, and so I went back to their story and created a more complex lineage, whereby they were turned into stone by a Romani witch and then eventually moved into a Turkish settlement. From there, I started more serious work on the language but had to keep returning to the story/world to better understand what words they might borrow and what they might hold important to them as a culture (to better inform their taboos, idioms, etc.).

The process gets even deeper when I started translating texts into the language because, for any word I didn’t already have in the language, I needed to return to the world and think about how the speakers would express that concept. Once you’ve created a language, it is much easier to understand how the books of Lord of the Rings were actually borne out of the languages Tolkien had created.

MC: What are some of your favorite examples of conlangs (either in popular culture or that your students have created).

JS: Tolkien’s languages are masterpieces. ‘Nuff said, right?

Paul Frommer’s Na’vi (created for Avatar) is beautiful, anything David J. Peterson creates is amazing (e.g., Dothraki, Irathient, Shiväisith…), and I adore Britton Watkin’s Siinyamda.

From my students, I’ve had a student create a language for bears based off a quote where someone pointed out how many words human languages have for bears and wondered how many words a bear might have for a human. She took that quote and ran with it, creating a language and culture for bears and did an amazing job with it. The paper detailing her language, ARKTOSK, even went on to win a university award.

Another student created a beautiful language for underwater creatures that has one of the prettiest writing systems I’ve seen created in my classes. Another student created a language for time-traveling aliens and went into such depth with his grammar that he created 11 grammatical tenses that allowed his speakers to distinguish between the “real” timeline and a personal timeline (e.g., yesterday I might have been in the future).

Yet another student asked what would have happened if French had won out as the language of choice in England (after the Norman Conquest) and what the language might look like today after being isolated from continental French (for political reasons) over the last millennium. Quite frankly, I could go on and on about examples from my students—they have continuously surprised and amazed me by their creativity.

MC: If someone wanted to try their hand at this, how might they start? What resources would you recommend?

JS: I’d recommend reading David J. Peterson’s The Art of Language Invention, which I think is the most valuable resource to date for someone new to conlanging (or even for someone who isn’t new but wants a fresh perspective on the art). If a person wanted to read more than one guide, I’d also recommend Mark Rosenfelder’s Language Creation Kit [MC: a starter version of which is available for free here], which provides practical advice for creating languages that is accessible to a wide audience.

I definitely recommend getting involved in a community of conlangers—you learn the most by asking questions of people who have already created languages and are still actively pursuing the art. For instance, the Language Creation Society offers conlangers a chance to meet at a biennial conference, local meet-ups for some locations, newsletters to keep up to date with each other, and even conlang relays (which are both educational and fun).

MC: From a teaching perspective, what concepts can we better understand about linguistics as we work through the invention of a language?

JS: Creating a language requires you to both conceptually understand linguistics and apply those concepts in a way that helps you better understand structures of language. I can’t count the number of times a student in my invented languages class will say something like, “I never understood Spanish tenses until now!” or “I thought I understood cases until I had to apply them in my language.” Conlanging gets your hands in language from the foundation up, allowing a window into the inner workings that studying a natural language from the outside can’t necessarily offer.

Thanks so much to Dr. Jessica Sams for taking the time to share her expertise. Dag dag!

Megan Condis is an Assistant Professor of Games Studies at Texas Tech University. Her book, Gaming Masculinity: Trolls, Fake Geeks, and the Gendered Battle for Online Culture, was released in May of 2018 by the University of Iowa Press. She blogs about popular culture at https://megancondis.wordpress.com/ or you can find her on Twitter @MeganCondis.

This article was first published on Unwinnable. Reprinting on Language at Play was possible with permission from the author, Megan Condis. If you liked reading it, follow Megan online, visit Unwinnable.com and consider subscribing!